In December 2024, after more than 35 years, I stopped working as a technical writer.

I hesitated to call myself “retired” because I wasn’t sure that was true. I felt burned out but didn’t know whether the burnout would last. Maybe I just needed some time.

A month or so after I stopped working, I published a collection of essays, poems, and short stories I’d worked on for years in my spare time. That was fun. I worked with an editor, learned about self-publishing, and published my book on Amazon. The entire endeavor took a few months.

After that, I did a lot of sitting around—so much so that I considered reentering the workforce. I even took a few interviews.

Retirement taught me what I already knew: I’m not a “project guy.”

I don’t have a workshop in my basement, I don’t tinker with cars, I’m not a hobbyist in any sense, and I’m about as “handy” as Captain Hook. So, retirement became a bit of a vacuum for me – a lot of time with nothing to fill it with.

To make things worse, my wife retired shortly after me, and it turns out that she is a “project guy (or gal).”

Unlike me, my wife finds things to do every day. She’s in constant motion – organizing the basement, digging in the garden, putting up bird feeders. I’d be sitting on the couch, watching the news or Sports Center, and I’d look up and see my energetic wife in the yard, weeding, feeding, and seeding with purpose.

I felt like a lazy lump. She’d come in from the outside with a smile on her face and say, “It’s a beautiful day out there,” not necessarily wanting me to join her but wanting me to at least get off my ass.

Caring for our dog Pepsi kept us both busy during those early months of retirement. We spent a lot of time and energy helping Pepsi navigate illnesses and old age until that dreadful day when we had to put her down. It was a tough time for both of us. I’m thankful I was retired when all of that went down.

Though I miss Pepsi immensely and miss the joy of k9 companionship in general, it was freeing not to have that 24/7 responsibility for the first time in 12 years. But after a few months, I began to think it would be nice to have a dog again, leading me to Rover.

Rover is a pet-sitting, boarding, and walking service.

I thought to myself, “I love dogs, I know I’d be good at this, it’s going to get me off my butt, and we have a pretty good setup logistically (large, enclosed back yard with two dog-loving people who are home all the time).

I’ve been a Rover rep since January 2025, providing mainly boarding services, but I’ve also walked a few dogs.

Rover allows me to set my schedule, so I can block off weeks or months at a time in case I do suddenly become a project guy (unlikely) or if my wife and I decide to take a vacation, all while putting some spending money in my pocket.

Rover helped fill the hole Pepsi’s death left in my heart with an opportunity for K9 companionship while providing a service to pet owners looking for a warm, safe, and loving environment for their pets.

Honestly, it’s been a win-win.

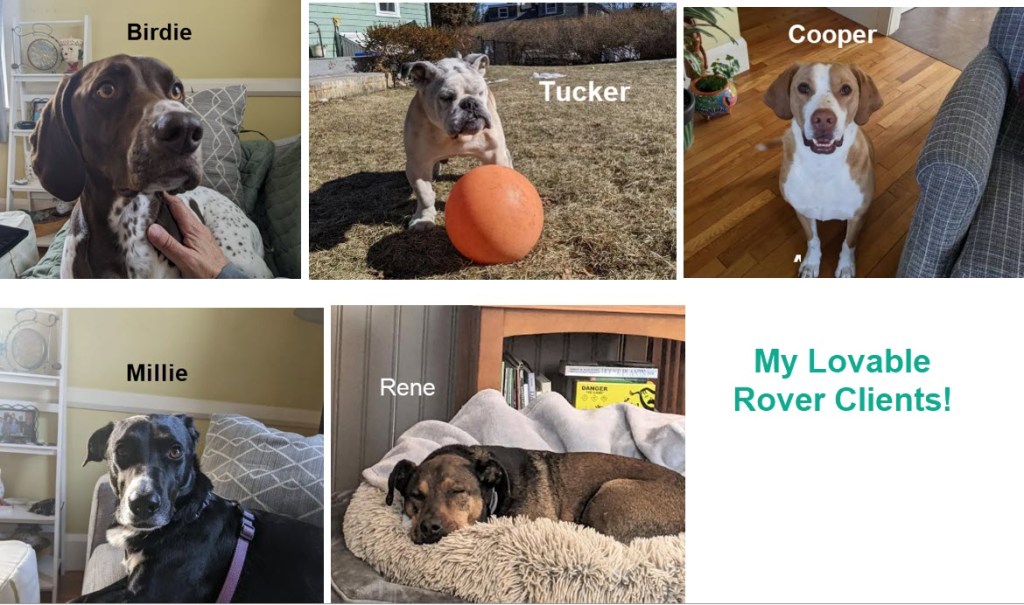

So far, my clients include a loveable and playful hound mix named Cooper, a quiet and reserved basset/shepherd mix named Rene, a timid lab mix named Millie, a gentle geriatric bulldog named Tucker, and an enthusiastic, boundlessly energetic, and inquisitive German Short Haired pointer named Birdie.

I’ve had several Meet and Greets that have resulted in bookings through the Summer.

Each dog has its own personality, and it’s been a joyful experience watching them adjust to me and learning how to adjust to them. All of the dogs I’ve boarded so far have acclimated fairly quickly—they become comfortable in a day or two.

Our house feels more like a home with a dog on the couch or sunning themselves on the back patio.

I’m sensitive to the fact that every dog that an owner drops off is probably feeling some anxiety, at least initially. My wife and I do our best to give the dogs the space to explore our house and become comfortable with new and unfamiliar surroundings. I try to keep the house quiet (maybe some soft music).

I’m discovering that when a dog is comfortable with where they are, they become comfortable with me, and that’s when I can begin building trust by going on walks, sitting together on the couch, or playing fetch in the backyard.

When it’s time for my K9 guests to leave, I feel a tinge of sadness, but mostly, I’m happy that I could provide them with a loving and welcoming place to stay while their owners are away.

Every pet owner I’ve dealt with has been great. I provide daily updates with videos and pictures and converse with them over the Rover app.

Being a Rover rep has been an emotionally uplifting experience while providing a much-needed distraction from the chaos in our country and the world.