I was tired. Take care of Daisy. Love, Dad.

That was the note (a sticky note, actually), pushed hard and pressed purposefully on the upper-left corner of the corkboard in his home office, now splattered with brain matter and blood – like a Jackson Pollock knockoff.

He woke that Tuesday to his routine—lying awake for several minutes before sitting up, scratching his dog Daisy behind the ear, and gesturing for her to get off the bed—but Daisy didn’t budge; she just thumps the mattress with her tail and yawns comfortably. She stares at him and, with her eyes, says, “Tell me again why we’re getting out of this wonderfully warm bed.”

He swings his legs over the side of the bed and stands, “Come on, girl, we’re burning daylight.”

They descend the narrow staircase slowly—her spine stiff with arthritis, his knees achy from age. “Aren’t we a pathetic pair?” he says. Daisy keeps her head down, focusing carefully on each step, but she wags her tail gently at the sound of his voice as if to say, “Yes, we are.” They reach the sunlit kitchen together. “Mission accomplished,” he says (only half-jokingly) and pets her softly.

She looks up at him warmly, tail wagging, eyes smiling.

It’s been four years since his wife passed, leaving him and Daisy to fend for themselves. He puts on a pot of coffee, opens the sliding glass door, and says, “Do your business,” as Daisy steps gingerly onto the patio and into the backyard.

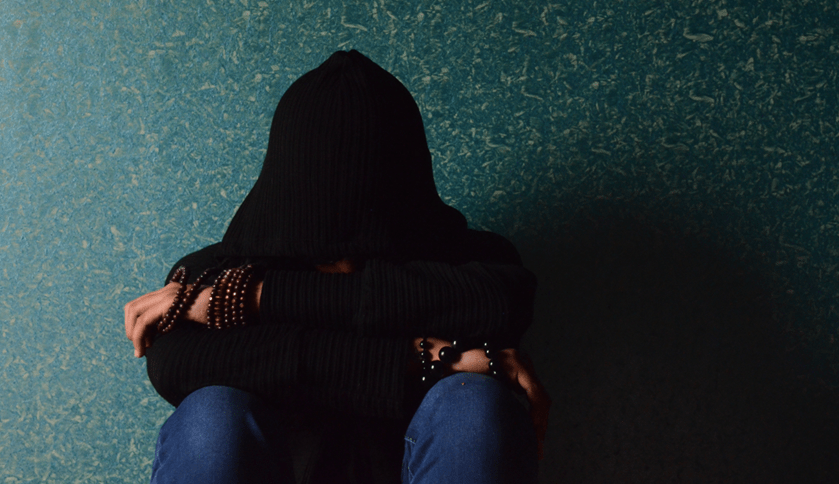

He glances at the manila envelope labeled Medical Imaging on the kitchen table; the clinically grim words: inoperable, terminal, three-to-six months, lurk in his thoughts like shadowy, hooded interlopers with ropes and daggers.

He pours himself a cup of coffee and steps onto the patio as Daisy patrols the yard’s perimeter. When he goes to sit, a searing pain from his belly to his back doubles him over, “fucking Christ,” he says through gritted teeth, imagining the tumors in his stomach rubbing against one another like malignant tangerines in a sack.

With trembling hands, he sets his coffee cup down and takes a deep, steadying breath until the pain subsides. He retrieves a pack of Marlboros from his flannel shirt pocket, lights up, and takes a long, satisfying drag while looking out over his backyard.

It’s always quiet at this time of day. Still, if you listen intently, you can hear the distant drone of early morning commuters—the wet rattle and hum of trucks and cars over potholes and puddles—while more closely, the thinly audible vibrations of birds and insects, their wings still wet with morning dew, dart through the yard before disappearing into the sun-kissed pines and maples that bordered his property.

In between drags, he sips and savors his dark roast, listening to the familiar, incongruent mashup of nature and civilization as Daisy slowly returns to him.

He’ll miss his mornings on the back patio with Daisy, but not enough to stick around for the metastasizing shit-show gathering in his gut. He knew immediately after his last doctor’s appointment that he wasn’t sticking around for that.

His children were grown and out of the house. He advised and counseled them directly and honestly about how to get on. In this regard, he felt accomplished. His parenting in the rearview made him feel he could exit this world with a clear conscience. “Mission accomplished,” he says under his breath, causing Daisy to look up at him curiously.

The afternoon comes quickly.

Daisy watches him sweep the kitchen floor. He pauses to look at her, struck by how time has touched his companion, from the floating cataract in her eye to the rounded and tanned teeth in her mouth.

He leans on his broom and speaks softly in Daisy’s direction, “From pearly whites to tiger’s eye, they tell the tale of you and I.” She thumps the floor with her tail.

He discards the small pile of crumbs and dog fur into the kitchen trashcan and gathers Daisy’s leash from the hall closet, “Are you ready, girl?” She perks up immediately. He slips a frayed collar decorated with dog bones and frisbees over her head. He clips the leash to it as Daisy wiggles with anticipation.

They walk out the front door together.

Even in her arthritic state, Daisy relishes their daily walk – nose to the ground, intently sniffing clover, dirt, thistle, and weed. An amalgam of scents blossoms into a bouquet of memories. Daisy responds with a spritelier gait, bringing a slow smile to her master’s face.

They end up where they always do – by the open farms and fields near their house. He unleashes Daisy and gives her free reign, but she never strays too far from his side. When they return home, he slips Daisy an extra half dose of pain medication to make her sleepy and tells her to lie down. She trots to her bed beneath the bay window in the living room, curls up contently, and closes her eyes.

He watches her until she falls asleep; at this point, he rises from his recliner, walks over to her quietly, gets on his hands and knees, kisses her on the head, and begins sobbing. The sound of his grief catches him off guard, and he immediately tries to suppress it, triggering his shoulders to tremble and quake. Daisy takes a deep breath but, to his relief, never opens her eyes. She’s everything to him.

He struggles to his feet and to compose himself before texting his sons to come to the house at 5:30 PM – ending the message with “It’s important.” Then, he tapes a brass key to a piece of paper torn from a legal pad, labels it Safety Deposit Box 347, and places it on the living room chair next to Daisy’s bed.

A few weeks back, he penned his wishes for Daisy in a letter addressed to his sons and placed it on top of the legal documents, trinkets, and keepsakes in that box. In the letter, he explains the reasoning behind his decision. He asks his sons to take good care of Daisy, keep with her routine as best they can, and, most importantly, walk her daily in the farms and fields by the house.

After reading his own words that day, he felt assured and comforted. He locked the box, put the key in his pocket, and walked out. As he passed the security officer guarding the vault, he winked and whispered, “Mission accomplished.”

With Daisy fast asleep, he walks into his office, sits in his chair, presses the sticky note onto the corkboard, retrieves a revolver from the desk drawer, puts the barrel to his temple, and pulls the trigger – never hesitating – not even for a second.

His actions played out gracefully, like a choreographed dance that he’d practiced in his head for months.

Daisy wakes momentarily to a sharp and unfamiliar popping sound. She raises her head and sniffs inquisitively at the burnt powder scent wafting above her. She looks around the living room and then towards the den and office. The door is closed. She whines for a bit before dozing off to the familiar sounds of home – the low hum of the refrigerator, the ticking clock in the living room, and the occasional knocks and pings from the furnace.

She opens her eyes a few hours later to two young men crying and cross-legged on the floor in front of her bed. She thumps her tail slowly, still under the effects of the medication.

They lean over in tandem, hug her, and tell her everything will be OK.