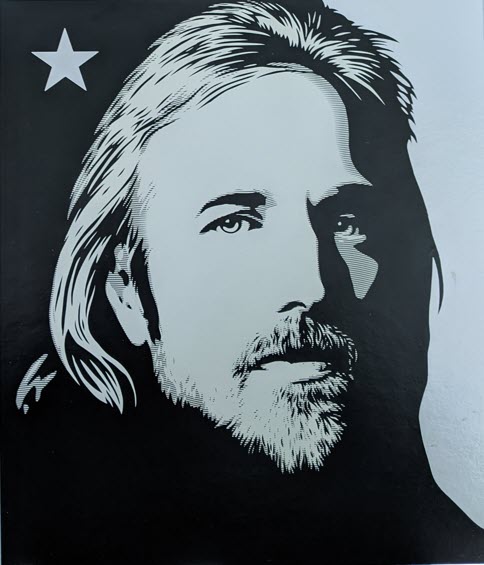

It’s been nearly six years (October 2, 2017) since Tom Petty died.

A few months before his passing, my son and I drove from Rhode Island to Philadelphia to catch Tom and the Heartbreakers on the final leg of their 40th Anniversary Tour.

On our way down to the show, we listened to every Heartbreakers album in sequence, amazed at the quantity of quality the band produced over their 40 years.

When Tom made his way to the microphone that night in front of a packed Wells Fargo arena — he seemed a little unsteady. His voice was thin and shaky when he addressed the audience, and I wondered if time had finally caught up to the rock icon.

That show was my sixth Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers concert. Like the previous five, I walked out of the arena blissfully. At 66 years old and on a fractured hip, Tom Petty remained true to his craft and the spirit of rock and roll. He and the band were brilliant.

For over 40 years, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers never cheated their audience with half-hearted performances or sub-par albums. They loved what they did, which showed in the studio and on stage.

That show in 2017 has me reminiscing on how and when I got hooked on the Heartbreakers.

The first Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers song I heard was Refuge in 1979 as a junior in high school. That song jolted with me the instant I heard it. My reaction to it bordered on chemical, and for three minutes and twenty-two seconds, I felt true clarity, like the music physically pushed shit aside in my head – so it was just me and the song.

I’m not sure why that song resonated so powerfully. Perhaps it was the convergence of Petty’s aggressive-edged delivery frenetically stirred by the tumult of adolescence and teenage angst.

I don’t know “the why,” but I remember “the when” like it happened yesterday.

I’m not sure how it began for my son. Maybe it was musical osmosis from exposure to A LOT OF Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers at an early age.

Perhaps my son connected with a specific song or album during adolescence and got hooked like I did.

Or maybe he saw Tom Petty as a musical bridge to span the sometimes-fractious waters between a father and son.

The most intriguing thing about this trip down memory lane is how Tom Petty evolved as an artist and the impact that had on me as a fan.

As much as I loved Refugee as a teenager, listening to that song as an adult was mainly a way of reconnecting with my youth. Sometimes, “reconnecting” is the extent of our relationship with an artist or song.

A more substantive relationship develops when the artist evolves – because that presents an opportunity to connect with them on a deeper level.

As Tom Petty matured, he became a master songwriter. His songs tapped into the complexities of human relationships with sparse and simple language. That’s what kept me tethered to him as an artist.

The way I connect with songs like Wildflowers and Square One is totally different than the nostalgic way I connect with Refugee or Here Comes My Girl – because I evolved as well (thankfully).

Tom’s evolution as an artist allowed his fans to grow with him — and most of us did.

And that’s why the relationship is impactful to so many people.